Other FIT Wellington pages:

- A New Public Transport Approach

- A Suggested Route

- Advocacy or Consultancy

- Are we on track

- Art of Light Rail Insertion

- Auckland Light Rail Options

- Briefing to Transport Minister

- Bus and Light Rail in Central Wellington

- Bus Rapid Transit is Unsuitable

- By the Numbers

- Can Light Rail Attract Enough Demand

- City of Well Connected Communities

- Comparing Canberra and Wellington

- Congestion Free Wellington

- Draft GPS on Land Transport

- Estimating Travel Time

- FIT Wellington

- Funding Light Rail

- Glossary

- Golden Mile Trial

- Letter to Capital Magazine

- LGWM Options Feedback

- LGWM Personal Submission

- LGWM Submission

- Light Rail Costs

- Light Rail Design Brief

- Light Rail FAQ

- Light Rail Options Survey

- Light Rail Planning Assumptions

- Light Rail to Lincolnshire Farms

- Making Tram-Train Work

- Mass Rapid Transit in Wellington

- Ministerial Talking Points

- Move More People with Fewer Vehicles

- Moving on from LGWM

- Myth Busters

- N2A Talking Points

- NZTA Talking Points

- Open Letter on Trackless Trams

- Open Letter to LGWM

- Paul Swain Monday 1 February 2016

- Planning Principles

- Public Transport in Wellington

- Public Transport Spine Issues

- Public Transport Spine Study

- Public Transport Spine Workshop

- SH 1 Wellington Improvements

- Spatial Plan Submission

- The Case for Light Rail

- Three Minute Summary

- Towards Low Emission Cities

- Track Gauge

- What Makes Light Rail Succeed

- What Next for Transport in Wellington

- Workshop Code of Conduct

Ten year vision

FIT Wellington stands for Fair, Intelligent Transport for Wellington. We are a group of Wellington citizens, who wish to see a change in the present culture where the private car dominates over cheaper, safer, more economic, healthy and climate-friendly transport alternatives.

PDF settings (show)

FIT’s vision for Wellington is a modern, vibrant city designed around the needs of people, not cars. This vision includes the following:

- A city that actively promotes walking, cycling and electric public transport to reduce transport costs, encourage physical exercise and mitigate against pollution and climate change effects.

- A healthy and safe city where the built environment, including its transport system, enhances the unique character and beauty of our harbour capital.

- A city where reliable, low-cost, fast and convenient public transport takes people to where they want.

- A city where modern light rail along key routes is an essential component of an overall transport plan.

- A city where the desired urban form is paramount.

Document purpose

FIT has summarised what we consider are the main issues that need to be investigated to advance light rail for Wellington, to provide a common basis for an informed discussion. While we have made every effort to check the facts presented here, bringing light rail to fruition will be a complex project, with many interrelated issues. We welcome constructive comments to correct any errors or omissions.

We assumed a 10 year planning horizon and focused on the Railway Station to Airport corridor. We also assumed GWRC will run the Matangi heavy rail units for their full economic life.

Background

The provisionally-named group WTF has developed suggestions on how to move Wellington forward.

Turn Lambton Quay into a PT/pedestrian space.

The golden mile is recognised as the main source of delays for bus services. Key steps are to remove cars and close the side streets to remove intersections. Put loading zones and disabled parking in the side streets, and also add people parks. It seems that in this new triennium this could have the support of WCC. In the past, the AA has supported a pedestrianised Lambton Quay.

Settle on a PT network.

Bring back in the consultant who did the original network plan, and get him to address the concerns that came up in consultation. In the end we won’t make everyone happy and get an efficient and optimal network, and at some point you have to fix it in place. The network has to be compatible with LRT introduction.

Sort out the issues that will arise with an efficient network.

Notably making hubs attractive, ensuring timetables make transfers quick, integrated ticketing, route numbering/legibility, accurate RTI, pedestrian linkages. The pain of the new network needs to be sorted out now, before LRT, so LRT is not blamed for that.

Make transit times predictable.

Use RTI data to identify where there are delays for buses and fix those through things like bus priority at lights, taking out parking, etc. A predictable transit time is the thing passengers want most.

Review the conclusions of the 2012 PTSS.

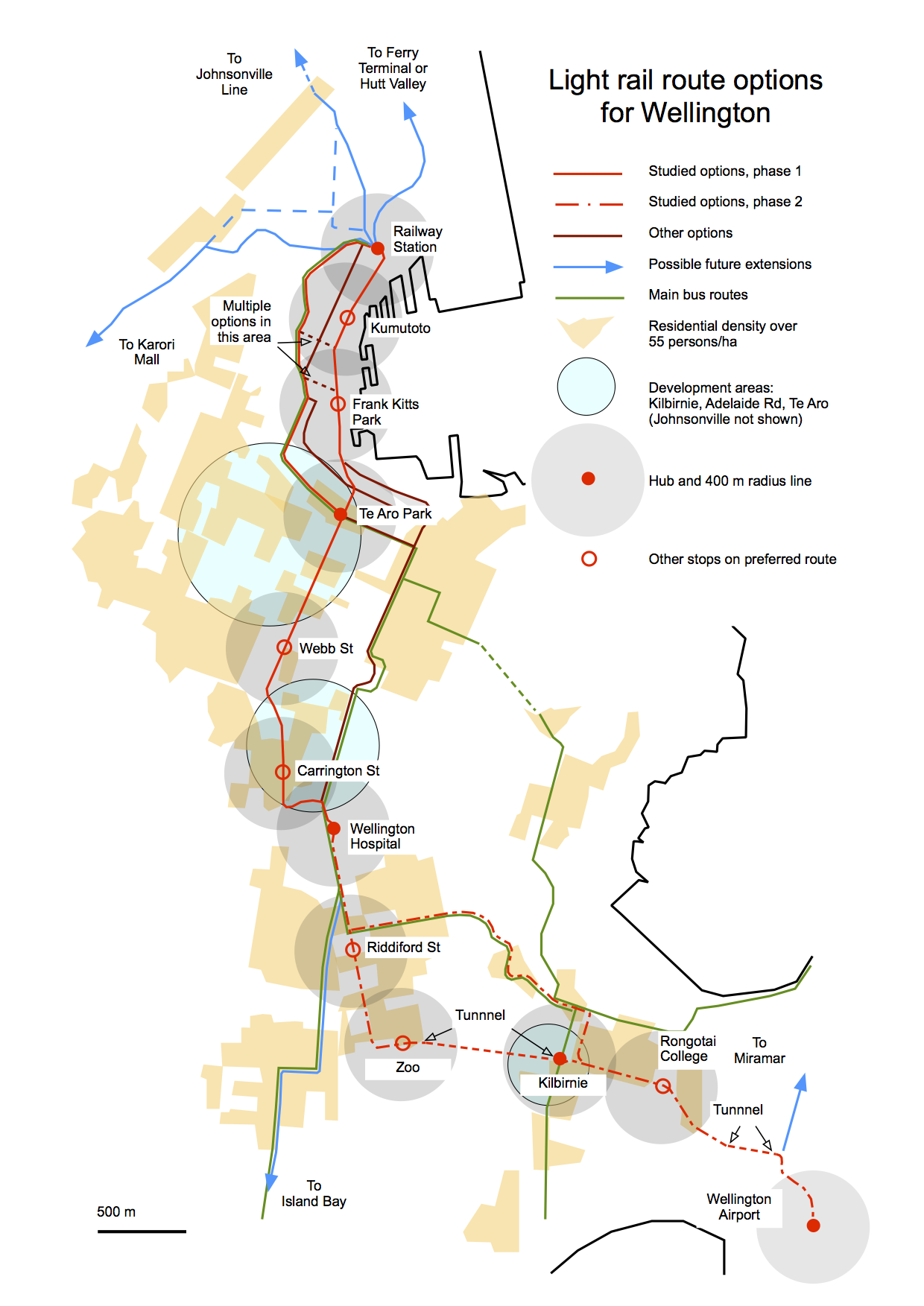

Much of the earlier technical work was fine, but the later stages were not. The benefit–cost ratio for the light rail option was a miniscule 0.05. However, this could be attributed to poor route selection and other factors. The Y shape chosen had several disadvantages: it loaded the costs of a second Mt Victoria tunnel onto light rail (and excluded the option of using Pirie Street and the existing Mt Victoria bus tunnel); it also did not take full advantage of aligning the PT spine to high growth residential areas such as Te Aro, Newtown, and Kilbirnie; and it did not allow for increase of patronage, whereas overseas experience is that introducing light rail can bring an immediate 25% increase in patronage because of improved service standards. A review by an international consultant with experience in design and operation of light rail and roading options is warranted.

Determine preferred route for PT spine and secure the route.

This would follow on from item 5 above and determine the best route for the PT spine from the Railway Station to the airport/eastern suburbs. It would examine options (e.g. Taranaki Street/Wallace Street/Newtown versus Kent and Cambridge Terraces/Adelaide Rd), recognising integration with urban design objectives for intensification and Transit Oriented Developments in places like Adelaide Rd, and opportunities for value uplift capture.

Consider timing issues.

Items 1 and 2 above are an immediate priority. Items 5 and 6 should be completed by the end of 2017 to allow for any funding provisions in the 2018 Long Term Plan. There would also be a need to examine potential funding solutions for light rail e.g. Government funding of 50% for public transport (as was agreed for Auckland’s City Rail Link) and commercial interests already expressed in a Public–Private Partnership. Subject to the above assessments, a desirable timing for light rail to be operational would be in 10 years. This would recognise the increase in capacity that light rail would provide and the contribution it would make to solving the Basin Reserve traffic congestion problems. A 10 year time frame would also coincide with the end of the new bus contracts.

Why Light Rail

Wellington needs to stay ahead of the gridlock being experienced in other cities. We need to make sure the nation’s capital continues to be one of the best places in the world to live, work, study, and play. We can’t build our way out of traffic congestion; high capacity public transport is essential.

Wellington relies on a single heavily overloaded bus route through the central city, carrying twice the desirable maximum passenger numbers and approaching a hard limit. Adding bus capacity will make the system slower and less reliable. As yet there are no published future route options.

Auckland’s Symonds St (4 lanes) carries about 120 buses an hour in the morning peak. AT is planning light rail because it considers anything over 100 buses an hour is overloaded. Wellington’s golden mile is already carrying 140 buses an hour.

Light rail is more adaptable to city streets than buses because high-capacity vehicles (5–8 times greater) can run less frequently. The only satisfactory alternatives to light rail are heavy rail, a second bus route, or BRT.

- Heavy rail would be a double-track extension south of the Railway Station, on the waterfront or in tunnel, probably too costly to be justified at projected demand.

- A second bus route would be short-term, as increasing demand would soon need a third: 6 lanes in total, half the present-day total of 12 lanes on the flat around the Old Bank.

- BRT as a high-capacity option needs four lanes (to allow for overtaking), as well as high priority and grade separation at busier junctions.

For avoidance of doubt, FIT assumes “light rail” refers to rapid rail transit, on a dedicated right-of-way with priority over other traffic at intersections. Stops are widely-spaced, 700–800 metres apart on average, strategically placed at locations of high demand. These criteria make service reliable, predictable, and fast. A trip from the airport to the railway station would take about 20–22 minutes.

Following the recent Paris and Marrakesh climate agreements, and record global average temperatures, it has become clear that high-capacity public transport systems—independent of fossil fuels—will soon bring cities significant economic advantages.

Route options

Simply replacing buses on the golden mile with light rail would require too many transfers. Wellington needs both modes, so a second 2-lane route must be found for light rail; i.e., four lanes to the trains—2 for buses, 2 for light rail. The main options for additional lanes are:

- Two lanes on the seaward side of the waterfront, for a fast route and minimal conflicts with turning traffic; intermediate stops could incorporate weather protection and street crossings;

- Two lanes on the city side of the waterfront; or

- Possibly The Terrace, Lambton Quay, or Featherston St.

Buses and light rail could share Lambton Quay—on separate lanes—as far south as Panama Street. However, the best option may be to reserve the golden mile for buses, which tend to carry two types of passenger who will not benefit from light rail, but are well-served by golden mile buses.

- Those using shorter bus routes, such as Brooklyn or Hataitai, who would be disadvantaged by required transfers: short trips cannot make up the time lost in transferring.

- Those who cannot walk far and appreciate closely-spaced bus stops with good access to both shops and offices.

Similarly, light rail passengers will tend to travel further and prefer predictability and speed. They will not wish to be delayed by frequent stops on the golden mile. If the preferred light rail route is Lambton Quay, buses would travel on Customhouse Quay south of Panama St to connect to Willis St (assuming it’s feasible to do so).

Separate routes in the central city require high-quality interchanges at either end. Passengers can then choose between making a transfer to minimise walking distance, or avoiding a transfer and perhaps walking further. The speed of a dedicated light rail route will to some extent offset transfer penalties.

All central city routes are at risk from sea level rise later this century. The first option (seaward side of the Quays) could run on a raised trackbed—say 1.5 m above ground level—and serve as a sea wall to protect the city. All light rail route options will need a vehicle depot.

Possible route extensions (none studied in any detail) include Miramar, Island Bay, Karori, Johnsonville, the Interislander terminal, and Hutt Valley. The Johnsonville Line is at present limited to trains at 15 minute intervals: too infrequent for light rail. Conversion would need double tracking and be very costly. Bypassing the Ngaio Gorge with a route beneath Tinakori Hill may be a cheaper option.

Funding options

Government has a policy of fully funding State Highway projects — the extra tunnels and highway to the airport will be part of SH1 — but not other transport projects. Auckland had a three year battle before Prime Minister Key finally agreed that Government would share funding of the City Rail Link, which is likely to be 50%. Under current policy, Government could not transfer funding from the RoNS account into light rail.

Wellingtonians expect the Government will fund the project in the same way as it funds light rail and city rail projects in Auckland.

- FIT and others have advocated for a robust, cost-effective ‘no frills’ light rail solution.

- Light rail would deliver three times the capacity of two Mt Victoria tunnels (12,000 people per hour versus 4,000 people per hour), for as low as half the $1+ bn price for the NZTA proposal of extra tunnels and a 4-lane highway to the airport.

- Therefore, there would be a substantial net benefit to the nation if the money was transferred from the RoNS account to fund light rail from the railway station to the airport. If both the strategic road and PT networks are serving essentially the same purpose, why shouldn’t they be funded the same way? Why should it matter what mode is being built if it’s considered a strategic network?

- If the Government is not prepared to agree to that transfer of funding from the RoNS account, we would still expect that the Government would pay 50% of the capital cost, in the same way that the Government has agreed to fund other major transport projects that are not state highways, e.g. Auckland City Rail Link.

- The remaining 50% of the capital cost would have to come from innovative funding sources or council borrowing (i.e., rate-payers for debt servicing). Possible funding sources for capital cost include:

- Infrastructure bonds, where community investors are prepared to accept a lower interest rate because the benefits flow back to the community. Pension funds are often cornerstone investors, for example in the Montréal light rail project scheduled to start construction in 2017.

- Value Uplift Capture (sometimes called “Tax Increment Financing”) — this approach is used commonly overseas in places like UK and USA. When new infrastructure like a light rail or subway line is constructed, the property values in the vicinity of the line and especially the stations go up dramatically. This represents a substantial windfall gain to the adjacent property owners. Value Uplift Capture is a method (like targeted rates) of capturing some of that uplift in value and reinvesting it in the infrastructure. In London, new subway lines and Cross Rail have been wholly or partly funded by this method.

- Australia has proposed charging motorists for their road use and using the money to fund urban rapid transit projects.

- There would need to be an early conversation involving the three partner organisations (GWRC, WCC and NZTA) with Government about these and other innovative funding mechanisms. It is of interest that the Mt Victoria Bus tunnel was totally funded by developers in Hataitai, and there have been a number of seminars in recent years on tax increment financing.

- The experience overseas is that light rail brings such a dramatic increase in the quality of PT service that, when it becomes operational, PT patronage increases significantly and substantial farebox recovery will help fund ongoing operating costs.

- Recognising the pressure on rate-payers, the objective would be to minimise the impact of light rail on rates, while maintaining affordable fares. The biggest cost component is the driver. Autonomous (self-driving) light rail systems often operate with no subsidy. We expect that in-street autonomous operation may be feasible by the time light rail comes to fruition in Wellington.

Planning issues

Successful light rail systems have high ridership, strong public support, and strong political support. These attributes only come about through careful planning and the political will to make change happen.

Introducing light rail to a new city can take up to 10 years from inception to the first line opening. As Background notes, the goal is to complete initial planning by the end of 2017, which means starting now. FIT suggests 3 activity tracks, advancing in parallel.

- The public engagement track covers activities associated with building public support for the project and overcoming objections. This includes a number of key messages, such as:

- Wellington cannot build its way out of traffic congestion—traffic always fills the space available

- light rail delivers cost-effective, congestion-free transport—3 times the capacity of ‘4 lanes to the planes’ for less cost

- construction disruption is temporary; congestion is forever—if we wait, disruption and congestion will increase

- The professional track covers activities associated with choosing the light rail route and securing the corridor for the future. This includes all aspects of the future urban form:

- route design to deliver ‘4 lanes to the trains’ with stop locations that optimise demand, access, travel times, and transfers at hubs such as the Railway Station

- street design to integrate the chosen route into the existing landscape, such as how intersection priority works (which may involve grade separation at busy intersections, signal lights, or barrier arms) and physical layout (such as using overhead wires or on-board batteries with charging at stops)

- The commercial track covers activities associated with funding the project and operating the system once it’s built. This includes:

- developing a realistic cost estimate for the prefered route and modelling the expected benefits

- forming a partnership across the local, regional and central arms of government and with cornerstone investors (public or private) and corporate sponsors to fund the project

- seeking expressions of interest from suitably qualified and experienced system designers, builders, asset owners, and system operators

The Get Welly Moving initiative is currently the vehicle for making the next generation of transport projects happen.

Technical issues

Vehicle costs can be reduced by placing a combined order with other cities, which in Wellington gives a strong incentive to order the same vehicles as Auckland. Both cities would benefit: a common design philosophy for new systems should cost less than separate approaches. Wellington alone is below the minimum order quantity needed to attract significant discounts.

Vehicle length need not be a concern. With modular designs it is a routine matter to add extra sections, either when purchasing or to increase capacity as patronage grows.

Two other issues might be anticipated.

- Vehicle width. The most usual figure is 2.65 m, but 2.4 m is also available from most suppliers. FIT’s limited experience is that 2.4 m would greatly simplify narrow routes such as Riddiford or Constable Streets.

- Track gauge. A shared order would be impractical if Wellington adopts ‘tram-train’ also running on KiwiRail tracks (other than the Johnsonville Line): an in-depth Dutch study concluded tram-train

is neither cheap nor easy.

Resolving these and other technical issues will necessarily require negotiation between those investing in the light rail project and the system suppliers. For now, they can be set to one side.