Other FIT Wellington pages:

- A New Public Transport Approach

- A Suggested Route

- Advancing Light Rail for Wellington

- Advocacy or Consultancy

- Are we on track

- Art of Light Rail Insertion

- Auckland Light Rail Options

- Briefing to Transport Minister

- Bus and Light Rail in Central Wellington

- Bus Rapid Transit is Unsuitable

- By the Numbers

- Can Light Rail Attract Enough Demand

- City of Well Connected Communities

- Comparing Canberra and Wellington

- Congestion Free Wellington

- Draft GPS on Land Transport

- Estimating Travel Time

- FIT Wellington

- Funding Light Rail

- Glossary

- Golden Mile Trial

- Letter to Capital Magazine

- LGWM Personal Submission

- LGWM Submission

- Light Rail Costs

- Light Rail Design Brief

- Light Rail FAQ

- Light Rail Options Survey

- Light Rail Planning Assumptions

- Light Rail to Lincolnshire Farms

- Making Tram-Train Work

- Mass Rapid Transit in Wellington

- Ministerial Talking Points

- Move More People with Fewer Vehicles

- Moving on from LGWM

- MRT Talking Points 2026

- Myth Busters

- N2A Talking Points

- NZTA Talking Points

- Open Letter on Trackless Trams

- Open Letter to LGWM

- Paul Swain Monday 1 February 2016

- Planning Principles

- Public Transport in Wellington

- Public Transport Spine Issues

- Public Transport Spine Study

- Public Transport Spine Workshop

- SH 1 Wellington Improvements

- Spatial Plan Submission

- The Case for Light Rail

- Three Minute Summary

- Towards Low Emission Cities

- Track Gauge

- What Makes Light Rail Succeed

- What Next for Transport in Wellington

- Workshop Code of Conduct

LGWM has announced 4 transport options aimed at moving more people with fewer vehicles, enabling more housing development, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In FIT Wellington’s view:

- Option 4, south coast light rail via Taranaki Street, is the strongest option and Option 2, bus rapid transit to the sea and skies, is the weakest option

- Option 1, south coast light rail + new public transport tunnel, is a stronger option than Option 3, south coast light rail

- leaving Vivian Street as the eastbound corridor for SH1 through traffic is a lost opportunity for unlocking the huge potential for developing the Te Aro precinct

- LGWM needs to find ways for radically shortening the implementation timetable

PDF settings (show)

The options are fair and reasonable

FIT understands that LGWM’s approach has been to match mass rapid transit mode to projected future demand. The options occupy the first 3 rungs of a demand ladder:

- lower growth, lower demand → bus priority

- medium growth, medium demand → 2-lane bus rapid transit

- higher growth, higher demand → streetcar-style light rail

- highest growth, highest demand → metro-style light rail (not used)

The approach focuses attention where it belongs — on decisions about the future development of the southern and eastern corridors. Frequent, fast services on high-capacity, low-floor vehicles, with on-platform ticketing, will operate on (mostly) dedicated and segregated lanes, with priority at intersections. The proposals will reduce the number of cars by reducing the number of lanes for cars. The outcome will transform the way we travel. FIT endorses this transit oriented development strategy.

FIT expects that when assessing the options, LGWM will use a risk-adjusted value approach. In all options, there is a risk that demand will be higher or lower than projected. The net benefit (benefits less costs) of each option needs to account for this risk by using the risk-adjusted net benefit.

Option 4 is the strongest option

FIT Wellington supports Option 4 because:

- it keeps options open for future mass rapid transit to the east via Cambridge Terrace, if and when demand on that corridor grows

- it includes Light Rail to Newtown and Island Bay along Taranaki Street, which is more central with more development opportunities than the more peripheral Cambridge Terrace

- it brings mass rapid transit within 400 metres (a 5 minute walk) of all points on the Golden Mile

- it bypasses the Basin Reserve, simplifying changes there to improve active transport options

- it is the lowest cost option, with the earliest completion date

Current best overseas practice is to build one light rail line at a time and to start design on the second line (mass rapid transit to the east) as soon as construction starts on the first line, and so on. Option 4 is consistent with this approach, which maximises development potential on each corridor.

Option 2 is the weakest option

We consider Option 2 is the weakest, highest risk option and should be discarded. If growth or mode-shift on the Island Bay corridor exceed LGWM’s projections, Wellington would face expensive, technically challenging and disruptive works to upgrade the corridor from BRT to light rail. Without such an upgrade, Wellington would have little choice other than progressively overloading the corridor with BRT vehicles, inevitably degrading system performance as buses get in each other’s way.

Longer buses are not practical. In contrast, it is relatively easy to increase the capacity of a light rail corridor by running longer vehicle-sets, with longer platforms. FIT notes and supports LGWM’s proposal to run a high frequency service, so there will be little opportunity to increase capacity by increasing frequency.

The risk that Option 2 has underestimated demand on the north–south corridor may be low probability, but the impact is very high. If demand significantly exceeds projections, the only mitigation is to upgrade the corridor. It is therefore essential that this risk is properly priced into the cost–benefit analysis for this option. One approach would be to include the risk-adjusted cost and benefit of upgrading the corridor to light rail.

Option 1 is stronger than Option 3

Compared to Option 3, Option 1 offers significant public transport improvements to the eastern suburbs, with better bus priority. Option 1 also provides a better layout at the Basin Reserve, including cross-platform transfers between the south (light rail) and east (bus priority) corridors. However, Option 1 is the most expensive option with potentially the longest delivery timetable. If demand on the eastern corridor significantly exceeds projections, upgrading the bus priority lanes to bus rapid transit would be relatively straightforward. However, upgrading to light rail may well be impractical.

Light rail to Island Bay can be improved

In reviewing the options presented, we saw several opportunities for enhancement:

- we were dismayed when we saw the long timelines for implementation and urge LGWM to identify options for radically shortening these timelines

- the route to Island Bay could become a genuine rapid transit route if light rail did not have to share its lanes with buses and other vehicles

- it would be easier to understand how future-proofed all the options are if LGWM gives some thought to how the mass rapid transit network will be extended in future (for example, to Karori)

- we favour a “MRT trunk, bus feeder” network design, rather than the “avoid transfers” approach that LGWM seems to have taken; reliable and frequent service overcomes transfer penalties

- it would be better to run light rail along Martin Square alongside the Pukeahu park rather than Haining Street, especially if SH1 traffic is rerouted from Vivian Street to Karo Drive, as discussed below

The light rail proposals are at the streetcar (slower) rather than the metro (faster) end of the light rail design spectrum. Experience in other cities teaches that people will walk farther to catch a faster service. FIT encourages LGWM to place stations further apart rather than closer together. Stations too close together compete with each other for the same riders and slow the service down. Stations too far apart create economic dead zones in between. We suggest stations at least 600 metres and at most 1 kilometre apart, with an aim of achieving an average speed greater than 25 kph.

Review the project scope

The previous government directed LGWM to omit from scope rerouting SH1 eastbound traffic off Vivian Street onto Karo Drive. FIT notes that the difference in cost between Option 1 (highest cost) and Option 4 (lowest cost) is $1.6bn. Without further analysis, FIT cannot have a properly-informed view on whether the additional cost is the best value for money.

Vivian Street is currently an example of a traffic sewer. We consider leaving Vivian Street as the eastbound corridor for through traffic is a lost opportunity for unlocking the huge potential for developing the Te Aro precinct. We support LGWM’s original proposal that eastbound traffic be routed along Karo Drive, making this a two-way thoroughfare from the Terrace Tunnel to the Basin Reserve.

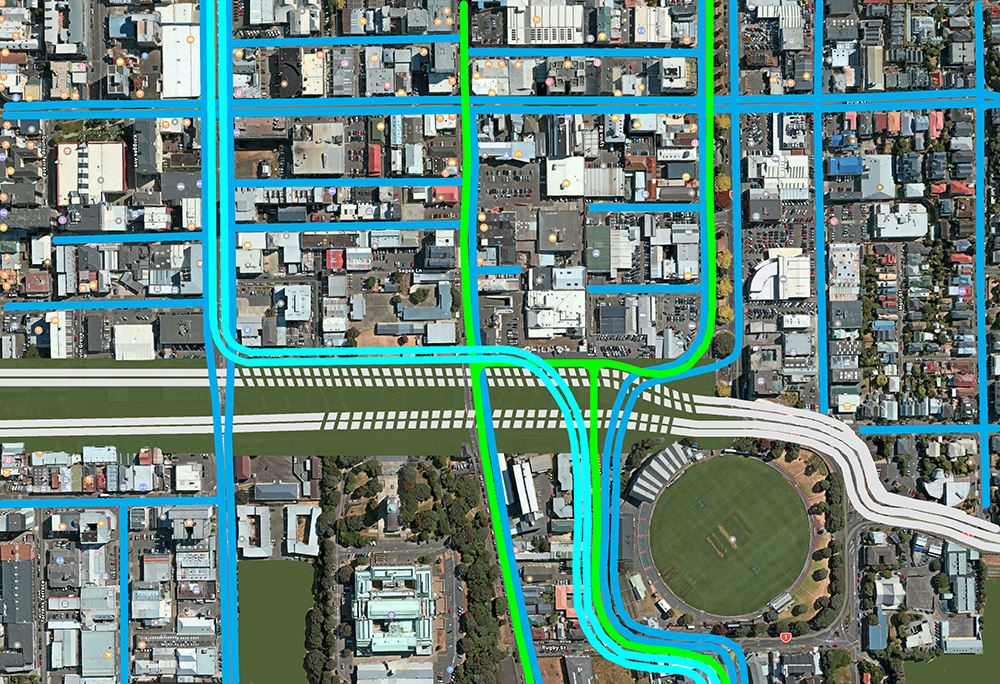

Eye of the Fish has published a layout that would be consistent with Option 4. How to liberate Vivian Street shows light rail (pale blue) running on Taranaki Street to Pukeahu park, where it runs parallel to a new eastbound SH1 trench (dashed white lines) to the west side of the Basin Reserve. Cycleways are shown in green, local roads are blue. Before LGWM chooses a preferred option, FIT would like to see how a future stage will liberate Vivian Street from eastbound SH1 traffic.

▴ How to liberate Vivian Street from SH1 (source: Eye of the Fish)

Depending on the projected development potential on the east–west corridor, either BRT or light rail may be an appropriate future upgrade to an initial implementation of bus priority. Running bus priority through the existing bus tunnel in the first instance would keep future options open and make the resulting upgrade works less challenging.

- ✒

- Michael Barnett

Convenor FIT Wellington