Other FIT Wellington pages:

- A New Public Transport Approach

- A Suggested Route

- Advancing Light Rail for Wellington

- Advocacy or Consultancy

- Are we on track

- Art of Light Rail Insertion

- Auckland Light Rail Options

- Briefing to Transport Minister

- Bus and Light Rail in Central Wellington

- Bus Rapid Transit is Unsuitable

- By the Numbers

- Can Light Rail Attract Enough Demand

- City of Well Connected Communities

- Comparing Canberra and Wellington

- Congestion Free Wellington

- Draft GPS on Land Transport

- Estimating Travel Time

- FIT Wellington

- Funding Light Rail

- Glossary

- Golden Mile Trial

- Letter to Capital Magazine

- LGWM Options Feedback

- LGWM Personal Submission

- LGWM Submission

- Light Rail Costs

- Light Rail Design Brief

- Light Rail FAQ

- Light Rail Options Survey

- Light Rail Planning Assumptions

- Light Rail to Lincolnshire Farms

- Making Tram-Train Work

- Mass Rapid Transit in Wellington

- Ministerial Talking Points

- Move More People with Fewer Vehicles

- Moving on from LGWM

- Myth Busters

- N2A Talking Points

- NZTA Talking Points

- Open Letter on Trackless Trams

- Open Letter to LGWM

- Paul Swain Monday 1 February 2016

- Planning Principles

- Public Transport in Wellington

- Public Transport Spine Issues

- Public Transport Spine Study

- Public Transport Spine Workshop

- SH 1 Wellington Improvements

- Spatial Plan Submission

- Three Minute Summary

- Towards Low Emission Cities

- Track Gauge

- What Makes Light Rail Succeed

- What Next for Transport in Wellington

- Workshop Code of Conduct

FITWellington.TheCaseForLightRail History

Show minor edits - Show changes to markup

- an all-up cost of $50 million per route kilometre (including depot and vehicles but excluding tunnels)

- an all-up cost of $50 million per route kilometre plus GST (including depot and vehicles but excluding tunnels)

- all costs exclude GST

- modular vehicles 2.65m wide and up to 63m long, with capacity for 470 passengers

- Invite proposals to build and run a CBD–Miramar service, carrying up to 10,000 passengers per hour and taking 20 minutes.

- Invite proposals to design, build and run a CBD–Miramar service, carrying up to 10,000 passengers per hour and taking 20 minutes.

- Christchurch’s heritage tram track came through the earthquakes almost unscathed. A contingency plan would be put in place to get light rail back up and running as soon as possible — likely to be in weeks or months, not years. In the meantime additional buses would be brought in immediately to replace light rail for a short period, so there would be no advantage in opting for a bus-based system in the long term over a light rail system.

- A contingency plan would be put in place to get light rail back up and running as soon as possible — likely to be a matter of months not years. In the meantime additional buses can be brought in within a few days to replace LRT for a short period, so there would be no advantage in opting for a bus based system in the long term over an LRT system. Christchurch’s heritage tram track came through the earthquakes almost unscathed.

(:description The current approach to public transport in Wellington is no longer tenable. Proposed investments in the bus system will bring welcome improvements, but will not achieve the step change in public transport patronage that Wellington needs. Our aim is to double ridership by progressively building a world-class light rail system in Wellington city. The best way to reduce congestion in Wellington is to encourage people out of private cars and buses onto light rail. The first stage, between the Railway Station and Miramar, via the Hospital and Airport, can be completed by 2030, for an estimated cost between $570 and $740 million, depending on the route. :)

(:description The current approach to public transport in Wellington is no longer tenable. Proposed investments in the bus system will bring welcome improvements, but will not achieve the step change in public transport patronage that Wellington needs. Our aim is to double ridership by progressively building a world-class light rail system in Wellington city. The best way to reduce congestion in Wellington is to encourage people out of private cars and buses onto light rail. The first stage, between the Railway Station and Miramar, via the Hospital and Airport, can be completed by 2030, for an estimated cost between $570 and $750 million, depending on the route. :)

FIT sees light rail as the essential infrastructure for realising this vision. Light rail is a form of public transport designed to provide fast, efficient, clean service to people living in urban areas. It uses electric rail cars, running on tracks in existing roads, separated from, and with priority over, other road traffic. It carries lots of people, with connections to buses and suburban trains at major interchanges. One light rail car can do the work of about 5 buses; adding segments can further lift capacity, while still allowing vehicles to negotiate sharp curves.

FIT sees light rail as the essential infrastructure for realising this vision. Light rail is a form of public transport designed to provide fast, efficient, clean service to people living in urban areas. It uses electric rail cars, running on tracks in existing roads, separated from, and with priority over, other road traffic. It carries lots of people, with connections to buses and suburban trains at major interchanges. One multi-segment light rail vehicle can carry as many passengers as about 7 buses, at twice the average speed.

- Use spaces (like roads) that the public already has a right to use, create dedicated lanes for light rail tracks, and give light rail the priority at intersections — other traffic always stops for trams.

- Use spaces (like roads) that the public already has a right to use, create dedicated lanes for light rail tracks, and give light rail the priority at intersections — except in emergencies, other traffic stops for trams.

While this approach to public transport is new to New Zealand, cities in other developed countries have been implementing it successfully since the 1980s. There is no reason to think Wellington will be any different.

While this approach to public transport is new to New Zealand, cities in other developed countries have been implementing it successfully since the 1970s. There is no reason to think Wellington will be any different.

- A contingency plan would be put in place to get light rail back up and running as soon as possible — likely to be in weeks or months, not years. In the meantime additional buses would be brought in immediately to replace light rail for a short period, so there would be no advantage in opting for a bus-based system in the long term over a light rail system. Light rail operates in other earthquake-prone cities, such as Vancouver and Tokyo.

- The Christchurch heritage tram tracks came through the earthquakes almost unscathed. A contingency plan would be put in place to get light rail back up and running as soon as possible — likely to be in weeks or months, not years. In the meantime additional buses would be brought in immediately to replace light rail for a short period, so there would be no advantage in opting for a bus-based system in the long term over a light rail system.

| 3.8km @ $50m/km | $190m | $190m | |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $38m | $38m | |

| Total | $228m | $228m |

| 4.1km @ $50m/km via Lambton Quay | $205m | − | |

| 3.8km @ $50m/km via waterfront | − | $190m | |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $41m | $38m | |

| Total | $246m | $228m |

| Grand Total | $737m | $570m | |

FIT acknowledges there are technical challenges in the Constable St option, but is confident that the engineers can find workable solutions. Clearly, the cost saving would be considerable — enough to fund over 3km of light rail construction. FIT suggests that the money may deliver better value if spent on extending the line north, e.g. to Johnsonville or Karori.

| Grand Total | $755m | $570m | |

FIT acknowledges there are significant technical challenges in the Constable St option, but is confident that the engineers can find workable solutions. Clearly, the cost saving would be considerable — enough to fund over 3km of light rail construction. The money may deliver better value if spent on extending the line north, e.g. to Johnsonville or Karori.

- Invite proposals to build and run a CBD–Miramar serviuce, carrying up to 10,000 passengers per hour, taking 20 minutes.

- Commit to and build the stage from the Hospital to Kilbirnie and Miramar, with a goal of opening the service to the public by 2030.

- Commit to and build the stage from the Hospital to Kilbirnie and Miramar, with a goal of opening the service to the public by 2027.

(:description The current approach to public transport in Wellington is no longer tenable. Proposed investments in the bus system will bring welcome improvements, but will not achieve the step change in public transport patronage that Wellington needs. Our aim is to double ridership by progressively building a world-class light rail system in Wellington city. The best way to reduce congestion in Wellington is to encourage people out of private cars and buses onto light rail. The first stage, between the Railway Station and Miramar, via the Hospital, can be completed by 2030, for an estimated cost between $640 and $850 million, depending on the route. :)

(:description The current approach to public transport in Wellington is no longer tenable. Proposed investments in the bus system will bring welcome improvements, but will not achieve the step change in public transport patronage that Wellington needs. Our aim is to double ridership by progressively building a world-class light rail system in Wellington city. The best way to reduce congestion in Wellington is to encourage people out of private cars and buses onto light rail. The first stage, between the Railway Station and Miramar, via the Hospital, can be completed by 2030, for an estimated cost between $570 and $740 million, depending on the route. :)

Light rail costs have fallen in recent years, and in 2014 the International Railway Journal quoted €25–30m per kilometre ($42–51m/km) for a typical line in France. Now Besançon, France has opened a new line for €17.5m/km ($30m/km). Using these figures as a guide, we consider the costs set out in This table are reasonable and conservative. The estimates recognise that civil engineering works cost more in New Zealand than overseas. We have assumed:

- an all-up cost of $60 million per route kilometre (including depot and vehicles but excluding tunnels)

Light rail costs have fallen in recent years, and in 2014 the International Railway Journal quoted €25–30m per kilometre ($42–51m/km) for a typical line in France. Now Besançon, France has opened a new line for €17.5m/km ($30m/km). The UK average is £21m/km ($37m/km). Using these figures as a guide, we consider the costs set out in This table are reasonable and conservative. The estimates recognise that civil engineering works cost more in New Zealand than overseas. We have assumed:

- an all-up cost of $50 million per route kilometre (including depot and vehicles but excluding tunnels)

| 3.8km @ $60m/km | $228m | $228m | |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $46m | $46m | |

| Total | $274m | $274m |

| 3.8km @ $50m/km | $190m | $190m | |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $38m | $38m | |

| Total | $228m | $228m |

| 2.3km @ $60m/km via Zoo | $138m | − |

| 1.6km @ $50m/km via Zoo | $80m | − |

| 2.2km @ $60m/km via Constable St | − | $132m | |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $56m | $26m | |

| Total | $338m | $158m | |

| Kilbirnie to Airport | |||

| 2.1km @ $60m/km | $126m | $126m | |

| 2.2km @ $50m/km via Constable St | − | $110m | |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $45m | $22m | |

| Total | $269m | $132m | |

| Kilbirnie to Miramar | |||

| 2.5km @ $50m/km | $125m | $125m | |

| Total | $241m | $211m | |

| Grand Total | $853m | $643m | |

FIT acknowledges there are technical challenges in the Constable St option, but is confident that the engineers can find workable solutions. Clearly, the cost saving would be considerable — enough to fund about 4km of light rail construction. FIT suggests that the money may deliver better value if spent on extending the line north, e.g. to Johnsonville or Karori, where tunnelling is unavoidable.

| Total | $240m | $210m | |

| Grand Total | $737m | $570m | |

FIT acknowledges there are technical challenges in the Constable St option, but is confident that the engineers can find workable solutions. Clearly, the cost saving would be considerable — enough to fund over 3km of light rail construction. FIT suggests that the money may deliver better value if spent on extending the line north, e.g. to Johnsonville or Karori, where tunnelling is unavoidable.

(:description The current approach to public transport in Wellington is no longer tenable. Proposed investments in the bus system will bring welcome improvements, but will not achieve the step change in public transport patronage that Wellington needs. Our aim is to double ridership by progressively building a world-class light rail system in Wellington city. The best way to reduce congestion in Wellington is to encourage people out of private cars and buses onto light rail. The first stage, between the Railway Station and the Airport, via the Hospital, can be completed by 2030, for an estimated cost between $650 and $890 million, depending on the route. :)

(:description The current approach to public transport in Wellington is no longer tenable. Proposed investments in the bus system will bring welcome improvements, but will not achieve the step change in public transport patronage that Wellington needs. Our aim is to double ridership by progressively building a world-class light rail system in Wellington city. The best way to reduce congestion in Wellington is to encourage people out of private cars and buses onto light rail. The first stage, between the Railway Station and the Airport, via the Hospital, can be completed by 2030, for an estimated cost between $650 and $850 million, depending on the route. :)

- Current spending on urban transport is primarily for greater motor vehicle use, which increases congestion by attracting new traffic onto already overcrowded streets. This is incompatible with good urban design and has high environmental, health and social costs.

- Slow and unreliable inner-city public transport, with few and poor-quality transfers, limits choice, discourages patronage, frustrates wider use of walking, and increases costs.

- Slow and unreliable inner-city public transport, with few and poor-quality transfers, limits choice, discourages patronage, frustrates wider use of walking, and increases costs.

- Current spending on urban transport is primarily for greater motor vehicle use, which increases congestion by attracting new traffic onto already overcrowded streets. This is incompatible with good urban design and has high environmental and social costs.

Compared with other New Zealand cities, such as Auckland, Christchurch and Dunedin, Wellington has good public transport patronage. However, Wellington remains far below international best practice. The potential to grow patronage is huge, but to achieve this growth, we need to make public transport an attractive and compelling alternative to the private car. Public transport must be competitive with the private car on quality and price. This means making public transport faster and more predictable, with seamless transfers between services and low fares.

Compared with other New Zealand cities, such as Auckland, Christchurch and Dunedin, Wellington has good public transport patronage. However, Wellington remains far below international best practice. The potential to grow patronage is huge, but to achieve this growth, we need to make public transport an attractive and compelling alternative to the private car. Public transport must be competitive with the private car on quality, timeliness and price. This means making public transport faster and more predictable, with seamless transfers between services and low fares.

The problem of moving traffic is primarily a peak hour one. Maximising capacity will never be achieved by expanding road space along the primary route from Ngauranga to the airport, nor by the proposals for BRT on key routes. Efficient movement of people and goods will only be achieved by introducing measures to reduce traffic volumes entering the city, particularly at peak hours. The best way to reduce congestion is by using congestion pricing to restrict parking and road space for private motor vehicle traffic, while making public transport more attractive.

The problem of moving traffic is primarily a peak hour one. Maximising capacity will never be achieved by expanding road space along the primary route from Ngauranga to the airport, nor by the proposals for BRT on key routes. Efficient movement of people and goods will only be achieved by introducing measures to reduce traffic volumes entering the city, particularly at peak hours. The best way to reduce traffic congestion is by using congestion pricing to restrict parking and road space for private motor vehicle traffic, while making public transport more attractive.

The proposed solution to Wellington’s public transport problem, BRT based on double-decker buses and an all-diesel bus fleet, will improve the service, but will do little to reduce bus congestion or bring about the step change in performance that Wellington needs. The time frame for electric buses is unknown and achieving full replacement could take much longer than expected. A proposal which ignores climate change and does not aim at quickly reducing CO2 emissions is not fit for purpose.

The proposed solution to Wellington’s public transport problem, BRT based on double-decker buses and an all-diesel bus fleet, will improve the service, but will do little to reduce bus congestion or bring about the step change in performance and patronage that Wellington needs. The time frame for electric buses is unknown and achieving full replacement could take much longer than expected. A proposal which ignores climate change and does not aim at quickly reducing CO2 emissions is not fit for purpose.

- Tie the city together. Light rail lines span the city from urban fringe to urban fringe, via the city centre.

- Use high-capability vehicles. That means large capacities, all-door entry, train-style fare payment before boarding, doors at platform level for easy access, and priority over other traffic.

- Have widely-spaced stops. Stops are far enough apart to improve travel times, but also serve critical transfer points where feeder buses or trains connect.

- Reach major destinations. Light rail lines emphasise access to education campuses, office complexes, hospitals, shopping areas, major suburbs, and the CBD.

- Tie the city together. Light rail lines span the city from urban fringe to urban fringe, via the city centre.

- Use high-capability vehicles. This means large capacities, all-door entry, train-style fare payment before boarding, doors at platform level for easy access, and priority over other traffic.

- Have widely-spaced stops. Stops are far enough apart to improve travel times, but also serve critical transfer points where feeder buses or trains connect.

- Reach major destinations. Light rail lines emphasise access to education campuses, office complexes, hospitals, shopping areas, major suburbs, and the CBD.

A line from the airport to the railway station via the hospital, continuing to Johnsonville, Karori, or Petone, is an initial work programme that satisfies these principles. The first proposed project, from the airport to railway station with connections to the commuter train network, will start to realise light rail’s benefits for Wellington and prove the concept. Johnsonville, Karori, and Petone are examples of options for future extensions.

A line from Miramar to the railway station via the hospital, continuing to Johnsonville, Karori, or Petone, is an initial work programme that satisfies these principles. The first proposed project, from the airport to railway station with connections to the commuter train network, will start to realise light rail’s benefits for Wellington and prove the concept. Johnsonville, Karori, and Petone are examples of options for future extensions.

- Use spaces (like roads) that the public already has a right to use, create dedicated lanes for light rail tracks, and give light rail the green light at intersections — other traffic always yields.

- Use spaces (like roads) that the public already has a right to use, create dedicated lanes for light rail tracks, and give light rail the priority at intersections — other traffic always stops for trams.

To be an attractive alternative to the private car, public transport must: go where lots of people are; be there when people need it; and make trips fast, predictable, and reliable. Light rail is the best way to do this. A light rail line has 3 times the capacity of a 4-lane highway. Trips between the Railway Station and Airport would take under 20 minutes.

To be an attractive alternative to the private car, public transport must: go where lots of people are; be there when people need it; and make trips fast, predictable, and reliable. Light rail is the best way to do this, offering 3 times the capacity of a 4-lane highway. Trips between the Railway Station and Airport would take under 20 minutes, with a tram every 5 minutes.

Overseas evidence shows that investing in light rail creates an economic halo around the stations along the corridor. The area within about 400 metres of a station becomes a focus for commercial, social and residential development. When stations are placed about 700–800 metres apart — closer together in the city centre, further apart in the suburbs, but always close to major destinations — the result is a rich and vibrant urban environment. This economic halo in turn drives light rail revenue growth.

Overseas evidence shows that investing in light rail creates an economic halo around the stations along the corridor. The area within about 400 metres of a station becomes a focus for commercial, social and residential development. When stations are placed about 800 metres apart — closer together in the city centre, further apart in the suburbs, but always close to major destinations — the result is a rich and vibrant urban environment. This economic halo in turn drives light rail revenue growth.

| Relocate underground services, Old Bank area | $30m | − | |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $52m | $46m | |

| Total | $310m | $274m |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $46m | $46m | |

| Total | $274m | $274m |

| Grand Total | $889m | $643m | |

FIT acknowledges there are technical challenges in the Constable St option, but is confident that the engineers can find workable solutions. Clearly, the cost saving would be considerable — enough to fund about 5km of light rail construction. FIT suggests that the money would deliver better value if spent on extending the line north, e.g. to Johnsonville or Karori, where tunnelling is unavoidable.

| Grand Total | $853m | $643m | |

FIT acknowledges there are technical challenges in the Constable St option, but is confident that the engineers can find workable solutions. Clearly, the cost saving would be considerable — enough to fund about 4km of light rail construction. FIT suggests that the money would deliver better value if spent on extending the line north, e.g. to Johnsonville or Karori, where tunnelling is unavoidable.

Light rail costs have fallen in recent years, and in 2014 the International Railway Journal quoted €25–30m per kilometre ($42–51m/km) for a typical line in France. Now Besançon, France has opened a new line for €17.5m/km ($30m/km). Using these figures as a guide, we consider the costs set out in This table are reasonable and conservative — civil engineering works tend to cost more in New Zealand than overseas. We have assumed:

- an all-up cost of $40 million per route kilometre (including depot and vehicles but excluding tunnels)

Light rail costs have fallen in recent years, and in 2014 the International Railway Journal quoted €25–30m per kilometre ($42–51m/km) for a typical line in France. Now Besançon, France has opened a new line for €17.5m/km ($30m/km). Using these figures as a guide, we consider the costs set out in This table are reasonable and conservative. The estimates recognise that civil engineering works cost more in New Zealand than overseas. We have assumed:

- an all-up cost of $60 million per route kilometre (including depot and vehicles but excluding tunnels)

- good project management and a “no-frills” approach to control nice-to-have costs (i.e. the lowest cost for a fit-for-purpose system)

| 3.8km @ $40m/km | $152m | $152m |

| 3.8km @ $60m/km | $228m | $228m |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $36m | $30m | |

| Total | $218m | $182m |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $52m | $46m | |

| Total | $310m | $274m |

| 2.3km @ $40m/km via Zoo | $92m | − |

| 2.3km @ $60m/km via Zoo | $138m | − |

| 2.2km @ $40m/km via Constable St | − | $88m | |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $47m | $18m | |

| Total | $283m | $106m |

| 2.2km @ $60m/km via Constable St | − | $132m | |

| Design & contingency (20%) | 567m | $26m | |

| Total | $338m | $158m |

| 2.1km @ $40m/km | $84m | $84m |

| 2.1km @ $60m/km | $126m | $126m |

| Planning, design & contingency (20%) | $32m | $26m | |

| Total | $191m | $160m | |

| Grand Total | $692m | $448m | |

This proposal should be relatively inexpensive to build, given good project management and a “no-frills” approach to control nice-to-have costs.

| Planning, design & contingency (20%) | $40m | $35m | |

| Total | $241m | $211m | |

| Grand Total | $889m | $643m | |

(:description The current approach to public transport in Wellington is no longer tenable. Proposed investments in the bus system will bring welcome improvements, but will not achieve the step change in public transport patronage that Wellington needs. Our aim is to double ridership by progressively building a world-class light rail system in Wellington city. The best way to reduce congestion in Wellington is to encourage people out of private cars and buses onto light rail. The first stage, between the Railway Station and the Airport, via the Hospital, can be completed by 2030, for an estimated cost as low as $450 million. :)

(:description The current approach to public transport in Wellington is no longer tenable. Proposed investments in the bus system will bring welcome improvements, but will not achieve the step change in public transport patronage that Wellington needs. Our aim is to double ridership by progressively building a world-class light rail system in Wellington city. The best way to reduce congestion in Wellington is to encourage people out of private cars and buses onto light rail. The first stage, between the Railway Station and the Airport, via the Hospital, can be completed by 2030, for an estimated cost between $450 and $700 million, depending on the route. :)

FIT stands for fair, intelligent transport. FIT’s vision for Wellington is a modern and vibrant city designed around the needs of people. Wellington will be:

FIT stands for fair, intelligent transport. FIT’s vision for Wellington is a modern, vibrant city designed around the needs of people. Wellington will be:

The current transport system over-privileges the needs of private motor vehicles, to the detriment of a reliable, fast and convenient public transport system. There are 3 problems which make this approach no longer sustainable.

The current Wellington transport system over-privileges the needs of private motor vehicles, to the detriment of a reliable, fast and convenient public transport system. There are 3 problems which make this approach no longer sustainable.

FIT’s proposal aims to double public transport use, increase walking and cycling, and halve urban motor vehicle use, thereby halving the carbon footprint per person from transport, by 2035. Shifting demand from private cars to public transport will free up road space for commercial vehicles. The way to make public transport more attractive is to make public transport faster and more predictable. FIT proposes to achieve this by creating an integrated, congestion-free public transport network in Wellington.

Wellington cannot build its way out of traffic congestion. FIT’s proposal aims to double public transport use, increase walking and cycling, and halve urban motor vehicle use, thereby halving the carbon footprint per person from transport, by 2035. Shifting demand from private cars to public transport will also free up road space for commercial vehicles. To make public transport more attractive, FIT proposes creating an integrated, congestion-free public transport network in Wellington.

To be an attractive alternative to the private car, public transport must: go where lots of people are; be there when people need it; and make trips fast, predictable, and reliable. Light rail is the best way to do this.

Light rail is a congestion-free transport mode. A well-designed light rail system can scale to absorb growth in passenger numbers without the system slowing down. This can be achieved by making the light rail cars longer with additional modules and by increasing the service frequency. Unlike buses, the time taken for people to get on and off does not increase as passenger numbers rise, so travel times stay the same and remain predictable. One multi-segment vehicle can potentially replace over 15 buses.

To be an attractive alternative to the private car, public transport must: go where lots of people are; be there when people need it; and make trips fast, predictable, and reliable. Light rail is the best way to do this. A light rail line has 3 times the capacity of a 4-lane highway. Trips between the Railway Station and Airport would take about 22 minutes.

Light rail is a congestion-free transport mode. A well-designed light rail system can scale to absorb growth in passenger numbers without the system slowing down. This can be achieved by making the light rail cars longer with additional modules and by increasing the service frequency. Unlike buses, the time taken for people to get on and off does not increase as passenger numbers rise, so travel times stay the same and remain predictable.

| Relocate underground services, Old Bank area | $20m | − | |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $34m | $30m | |

| Total | $206m | $182m |

| Relocate underground services, Old Bank area | $30m | − | |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $36m | $30m | |

| Total | $218m | $182m |

| Grand Total | $690m | $444m | |

| Grand Total | $702m | $444m | |

| Stage | Cost item | 2a | 2b |

|---|

| Stage | Cost item | 1a, 2a | 1b, 2b |

|---|

| Design & contingency (20%) | $30m | $30m | |

| Total | $182m | $182m |

| Relocate underground services, Old Bank | $20m | − | |

| Design & contingency (20%) | $34m | $30m | |

| Total | $206m | $182m |

| Grand Total | $656m | $444m | |

| Grand Total | $690m | $444m | |

FIT acknowledges there are technical challenges in the Constable St option, but is confident that the engineers can find workable solutions. Clearly, the cost saving would be considerable — enough to fund about 5km of light rail construction. FIT suggests that the money would deliver better value if spent on extending the line north, e.g. to Johnsonville, where tunnelling is unavoidable.

FIT acknowledges there are technical challenges in the Constable St option, but is confident that the engineers can find workable solutions. Clearly, the cost saving would be considerable — enough to fund about 5km of light rail construction. FIT suggests that the money would deliver better value if spent on extending the line north, e.g. to Johnsonville or Karori, where tunnelling is unavoidable.

- Greater Wellington puts light rail back in the 10 year transport plan and secures central government funding for the initial Railway Station to Airport project.

- Greater Wellington puts light rail back in the 10 year transport plan and secures funding for the initial Railway Station to Airport project.

FIT sees light rail as the essential infrastructure for realising this vision. Light rail is a form of public transport designed to provide fast, efficient, clean service to people living in urban areas. It uses electric rail cars, running on tracks in existing roads, separated from, and with priority over, other road traffic. It carries lots of people, with connections to buses and suburban trains at major interchanges. One light rail car can do the work of about 5 buses; multi-segment vehicles further lift capacity.

FIT sees light rail as the essential infrastructure for realising this vision. Light rail is a form of public transport designed to provide fast, efficient, clean service to people living in urban areas. It uses electric rail cars, running on tracks in existing roads, separated from, and with priority over, other road traffic. It carries lots of people, with connections to buses and suburban trains at major interchanges. One light rail car can do the work of about 5 buses; multi-segment vehicles further lift capacity, while keeping the ability to negotiate sharp curves.

The problem of moving traffic is primarily a peak hour one. Maximising capacity will never be achieved by expanding road space along the primary route from Ngauranga to the airport, nor by the proposals for BRT on key routes. Efficient movement of people and goods will only be achieved by introducing measures to reduce traffic volumes entering the city, particularly at peak hours. The best way to reduce congestion is to restrict parking and road space for private motor vehicle traffic with congestion pricing, while making public transport more attractive.

The problem of moving traffic is primarily a peak hour one. Maximising capacity will never be achieved by expanding road space along the primary route from Ngauranga to the airport, nor by the proposals for BRT on key routes. Efficient movement of people and goods will only be achieved by introducing measures to reduce traffic volumes entering the city, particularly at peak hours. The best way to reduce congestion is by using congestion pricing to restrict parking and road space for private motor vehicle traffic, while making public transport more attractive.

- Promote transit-oriented development along the light rail corridor and at stations; and

- Promote transit-oriented development along the light rail corridor and around stops; and

A line from the airport to Johnsonville or Karori, via the hospital and railway station, is an initial work programme that satisfies these principles. The first proposed project, from the airport to railway station with connections to the commuter train network, will partially realise light rail’s benefits for Wellington and prove the concept in Wellington. Johnsonville and Karori are among several options for future extensions.

A line from the airport to the railway station via the hospital, continuing to Johnsonville, Karori, or Petone, is an initial work programme that satisfies these principles. The first proposed project, from the airport to railway station with connections to the commuter train network, will start to realise light rail’s benefits for Wellington and prove the concept. Johnsonville, Karori, and Petone are examples of options for future extensions.

Freeing up space for light rail in Wellington’s often narrow streets will be achieved by moving on-street parking off-street, restricting vehicle access, and reducing the number of buses through the city centre. The price of central city parking and congestion charges will be instrumental in giving drivers an incentive to leave their cars at home and take public transport.

Freeing up space for light rail in Wellington’s often narrow streets will be achieved by moving on-street parking off-street, limiting vehicle access, and reducing the number of buses through the city centre. The price of central city parking and congestion charges will be instrumental in giving drivers an incentive to leave their cars at home and take public transport.

Light rail is a congestion-free transport mode. A well-designed light rail system can scale to absorb growth in passenger numbers without the system slowing down. This can be achieved by making the light rail cars longer with additional modules and by increasing the service frequency. Unlike buses, the time taken for people to get on and off does not increase as passenger numbers rise, so travel times do not increase and remain predictable. One multi-segment vehicle can potentially replace over 15 buses.

Overseas evidence shows that investing in light rail creates an economic halo around the stations along the corridor. The area within about 400 metres of a station becomes a focus for commercial, social and residential development. When stations are placed about 700–800 metres apart — closer together in the city centre, further apart in the suburbs, but always at major destinations — the result is a rich and vibrant urban environment. This economic halo in turn drives light rail revenue growth.

Light rail is a congestion-free transport mode. A well-designed light rail system can scale to absorb growth in passenger numbers without the system slowing down. This can be achieved by making the light rail cars longer with additional modules and by increasing the service frequency. Unlike buses, the time taken for people to get on and off does not increase as passenger numbers rise, so travel times stay the same and remain predictable. One multi-segment vehicle can potentially replace over 15 buses.

Overseas evidence shows that investing in light rail creates an economic halo around the stations along the corridor. The area within about 400 metres of a station becomes a focus for commercial, social and residential development. When stations are placed about 700–800 metres apart — closer together in the city centre, further apart in the suburbs, but always close to major destinations — the result is a rich and vibrant urban environment. This economic halo in turn drives light rail revenue growth.

- A contingency plan would be put in place to get light rail back up and running as soon as possible — likely to be a matter of months not years. In the meantime additional buses would be brought in immediately to replace light rail for a short period, so there would be no advantage in opting for a bus-based system in the long term over a light rail system. Light rail operates in other earthquake-prone cities, such as Vancouver and Tokyo.

- A contingency plan would be put in place to get light rail back up and running as soon as possible — likely to be a matter of weeks or months. In the meantime additional buses would be brought in immediately to replace light rail for a short period, so there would be no advantage in opting for a bus-based system in the long term over a light rail system. Light rail operates in other earthquake-prone cities, such as Vancouver and Tokyo.

We have identified feasible and affordable options for light rail and a supporting bus network, but have not identified a best or preferred option, which should await further study and public input. We propose buses and light rail on fully separated routes, both on or close to the Golden Mile. Interchanges enable easy transfer between bus and light rail services.

We have identified feasible and affordable options for light rail and a supporting bus network, but have not identified a best or preferred option, which should await further study and public input. We propose buses and light rail on separated routes, both on or close to the Golden Mile. Interchanges enable easy transfer between bus and light rail services.

The route is within the area defined in the N2A study, but avoids the Basin Reserve. Multi-segment light rail cars can be difficult on large, multi-lane roundabouts. This corridor is more suited to buses, with no over-riding reason to run high-capacity light rail that way. The choice is between serving the Massey Campus on Wallace St or the schools and proposed high density development on Adelaide Rd. The Adelaide Rd option warrants further investigation before finalising the route.

The route is within the area defined in the N2A study, but avoids the Basin Reserve. Multi-segment light rail cars can be difficult on large, multi-lane roundabouts. This corridor is more suited to buses, with no over-riding reason to run high-capacity light rail that way. The choice is between serving the Massey Campus on Wallace St or the schools and proposed high-density development on Adelaide Rd. The Adelaide Rd option warrants further investigation before finalising the route.

The flexibility of buses, often stated as a strength, is their weakness. Car drivers and delivery vehicles can park in priority lanes in the knowledge that buses can always drive around them. At signals, buses usually have to blend in with other road traffic to get through intersections — even when they are given special priority, they are still treated as just another road vehicle.

The flexibility of buses, often stated as a strength, is their weakness. Car drivers and delivery vehicles can park in priority lanes in the knowledge that buses can always drive around them. At signals, buses usually have to blend in with other road traffic to get through intersections — even when they are given priority, they are still treated as just another road vehicle.

We have identified feasible and affordable options for light rail and a supporting bus network. We are confident that we have workable options, combining buses and light rail, but have not identified a best or preferred option. We propose buses and light rail on fully separated routes, both on or close to the Golden Mile. Interchanges enable easy transfer between bus and light rail services.

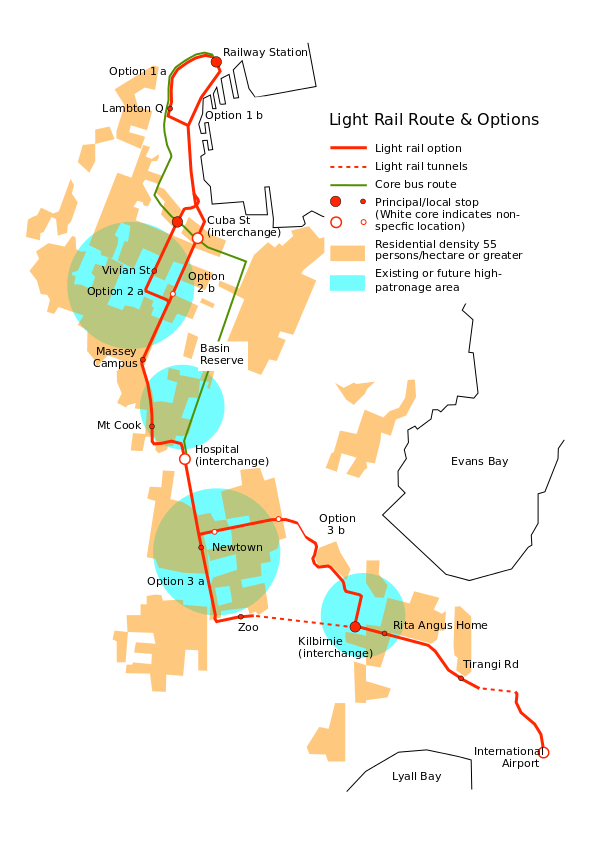

We have identified a single light rail route from the Railway Station to Wellington Hospital, Kilbirnie and Wellington Airport, with options in three places: south of the Railway Station; the Michael Fowler Centre; and Wellington Hospital. See This figure. Only the last option, 3a or 3b, will materially affect costs. Further investigation is needed to develop and cost a preferred route beyond the Railway Station.

We have identified feasible and affordable options for light rail and a supporting bus network, but have not identified a best or preferred option, which should await further study and public input. We propose buses and light rail on fully separated routes, both on or close to the Golden Mile. Interchanges enable easy transfer between bus and light rail services.

We have identified a single light rail route from the Railway Station to Wellington Hospital, Kilbirnie and Wellington Airport. See This figure. There are options in three places: Lambton Quay (1a) or Customhouse Quay (1b); Cuba St (2a) or Taranaki St (2b); and Mt Albert tunnel (3a) or Constable St (3b). Only the last option will materially affect costs. Further investigation is needed to develop and cost a preferred route beyond the Railway Station.

The identified route is within the area defined in the N2A study, but avoids the Basin Reserve. Recent experience suggests it will be challenging to find an acceptable Basin route, and multi-segment light rail cars can be difficult on large, multi-lane roundabouts. This corridor is more suited to buses, with no particular reason to run a high-capacity light rail route that way.

The identified route is within the area defined in the N2A study, but avoids the Basin Reserve. Multi-segment light rail cars can be difficult on large, multi-lane roundabouts. This corridor is more suited to buses, with no particular reason to run a high-capacity light rail route that way. The choice is between serving the Massey Campus or the proposed high density development on Adelaide Road.

This proposal should be relatively inexpensive to build, given good project management and a “no-frills” approach to control of nice-to-have costs.

This proposal should be relatively inexpensive to build, given good project management and a “no-frills” approach to control nice-to-have costs.

FIT proposes investing in light rail as essential infrastructure for realising this vision. Light rail is a form of public transport designed to provide fast, efficient, clean service to people living in urban areas. It uses electric rail cars, running on tracks in existing roads, separated from, and with priority over, other road traffic. It carries lots of people, with connections to buses and suburban trains at major interchanges. One light rail car can do the work of about 5 buses; multi-segment vehicles further lift capacity.

FIT sees light rail as the essential infrastructure for realising this vision. Light rail is a form of public transport designed to provide fast, efficient, clean service to people living in urban areas. It uses electric rail cars, running on tracks in existing roads, separated from, and with priority over, other road traffic. It carries lots of people, with connections to buses and suburban trains at major interchanges. One light rail car can do the work of about 5 buses; multi-segment vehicles further lift capacity.

- International agreement on climate change requires a new approach to sustainable transport that eliminates burning of fossil carbon by 2050 or shortly thereafter (urban traffic uses almost 20% of New Zealand’s fossil fuel).

- International agreement on climate change requires a new approach to sustainable transport that eliminates burning of fossil carbon by 2050, or shortly thereafter (urban traffic uses almost 20% of New Zealand’s fossil fuel).

- Spending on urban transport is primarily for greater motor vehicle use, which increases congestion by attracting new traffic onto already overcrowded streets, is incompatible with good urban design, and has high environmental and social costs.

When measured against the public transport systems in other New Zealand cities, such as Auckland, Christchurch and Dunedin, Wellington has a good public transport system, with good patronage. However, Wellington remains far below international best practice in other cities around the world, such as Zürich. The potential to grow patronage is huge, but to achieve this growth, we need to make public transport an attractive and compelling alternative to the private car. This means making public transport faster and more predictable, with seamless transfers between services, and offering competitive fare structures.

FIT’s proposal aims to double public transport use, together with increased walking and cycling, and halve urban motor vehicle use, thereby halving the carbon footprint per person from transport, by 2035. FIT proposes to achieve this by creating an integrated, congestion-free public transport network in Wellington.

- Current spending on urban transport is primarily for greater motor vehicle use, which increases congestion by attracting new traffic onto already overcrowded streets. This is incompatible with good urban design and has high environmental and social costs.

Compared with other New Zealand cities, such as Auckland, Christchurch and Dunedin, Wellington has good public transport patronage. However, Wellington remains far below international best practice. The potential to grow patronage is huge, but to achieve this growth, we need to make public transport an attractive and compelling alternative to the private car. Public transport must be competitive with the private car on quality and price. This means making public transport faster and more predictable, with seamless transfers between services and low fares.

FIT’s proposal aims to double public transport use, increase walking and cycling, and halve urban motor vehicle use, thereby halving the carbon footprint per person from transport, by 2035. Shifting demand from private cars to public transport will free up road space for commercial vehicles. FIT proposes to achieve the aims by creating an integrated, congestion-free public transport network in Wellington.

The proposed solution to Wellington’s public transport problem, BRT based on double-decker buses and an all-diesel bus fleet, will improve the service, but will do little to reduce bus congestion or bring about the step change in performance that Wellington needs. The time frame for electric buses is unknown and achieving full replacement could take much longer than expected. A proposal which ignores climate change and does not aim to reduce CO2 emissions is not fit for purpose.

While BRT can work well, Greater Wellington has acknowledged that the BRT system proposed is so low grade it is not Gold, Silver or Bronze standard, and does not even qualify as “BRT-light”. The system will make only a marginal difference to operating conditions in the city centre. It is cheap but ineffective. Even when BRT is implemented properly, it does not achieve the ride quality a rail-based system delivers. As a result, many people are not prepared to get on a bus but they will get on light rail.

BRT is a poor substitute for, and rarely produces anything like the benefits of, light rail. Whenever it gets difficult the traffic engineers give up and send the bus into the general traffic lanes — if it’s a light rail car, the system has to be engineered from end to end. Wellington cannot afford to waste time and money developing solutions that won’t produce the benefits that light rail can deliver.

The proposed solution to Wellington’s public transport problem, BRT based on double-decker buses and an all-diesel bus fleet, will improve the service, but will do little to reduce bus congestion or bring about the step change in performance that Wellington needs. The time frame for electric buses is unknown and achieving full replacement could take much longer than expected. A proposal which ignores climate change and does not aim at quickly reducing CO2 emissions is not fit for purpose.

While BRT can work well, Greater Wellington has acknowledged that the BRT system proposed is low grade and below Gold, Silver or Bronze standard. It does not even qualify as “BRT-light”. The system will make only a marginal difference to operating conditions in the city centre. It is cheap but ineffective. Even should BRT be implemented properly, it will not achieve the ride quality of a rail-based system. Overseas experience shows that people who are not prepared to get on buses will get on light rail.

In cities like Wellington with narrow streets, BRT is a poor substitute for light rail. Overseas, whenever it gets difficult the traffic engineers give up and send the bus into the general traffic lanes — if it’s a light rail car, the system has to be engineered from end to end. The need to move to low carbon transport is urgent. Wellington cannot afford to waste time and money developing solutions which won’t produce the benefits light rail can deliver.

The flexibility of buses is their weakness. They can always be diverted or rerouted, so there is no certainty in the minds of the public about where they operate. Car drivers and delivery vehicles can park in priority lanes in the knowledge that the bus can always drive around them. At signals, buses usually have to blend in with other road traffic to get through intersections — even when they are awarded special priority, they are still treated as just another road vehicle.

There is no realistic prospect of improving the situation in Wellington unless additional rail investment is made. If Greater Wellington seriously wants to get more people on public transport, it will be much easier with light rail than with any bus-based system. For example, patronage growth in the 30 French cities with light rail systems far exceeds patronage growth in cities that rely on buses.

The flexibility of buses, often stated as a strength, is their weakness. Car drivers and delivery vehicles can park in priority lanes in the knowledge that the bus can always drive around them. At signals, buses usually have to blend in with other road traffic to get through intersections — even when they are awarded special priority, they are still treated as just another road vehicle.

Overseas experience shows that if Greater Wellington seriously wants to get more people on public transport, light rail will triumph over any bus-based system. For example, patronage growth in the 30 French cities with light rail systems far exceeds patronage growth in cities that rely on buses.

- increased accessibility, e.g. for those using wheelchairs or pushing prams

- increased accessibility, e.g. for those using wheelchairs or pushing prams, or who do not own cars

- Light rail will only run on a few specially selected and well-designed streets. We are not proposing to replace the entire bus network with light rail — just to supplement the buses with an additional high-capacity cross-city corridor. Existing bus routes would be reconfigured to connect with light rail at major interchanges. Many European cities, such as Freiburg in Germany, run light rail on streets as narrow as those in Wellington.

- Light rail will only run on a few specially selected and well-designed streets. We are not proposing to replace the entire bus network with light rail — just to supplement the buses with an additional high-capacity cross-city corridor. Existing bus routes would be reconfigured to connect with light rail at major interchanges. Many European cities run light rail on streets as narrow as those in Wellington.

- There is no point bringing overseas visitors to the airport and convention centre without an efficient way of connecting them. What light rail does is provide the city with a suitable international image to complement other needed investments to grow the economy. Visitors expect light rail as an essential part of a modern, smart city. New Zealand and Wellington can afford anything it wants in the field of transport — like the $3bn+ being spent on Transmission Gulley and $1bn+ on the Ngauranga to Airport road corridor.

- There is no point bringing overseas visitors to the airport and convention centre without an efficient way of connecting them. What light rail does is provide the city with a suitable international image — visitors expect light rail as an essential part of a modern, smart city. New Zealand and Wellington can afford anything it wants in the field of transport, like the $3bn+ being spent on Transmission Gulley and $1bn+ proposed for the Ngauranga to Airport road corridor.

- A contingency plan would be put in place to get light rail back up and running as soon as possible — likely to be a matter of months not years. In the meantime additional buses would be brought in immediately to replace light rail for a short period, so there would be no advantage in opting for a bus-based system in the long term over a light rail system. Light rail operates in other earthquake-prone cities, such as Vancouver, Canada.

- Light rail is for the long term — Wellington is not dense enough to support light rail.

- A contingency plan would be put in place to get light rail back up and running as soon as possible — likely to be a matter of months not years. In the meantime additional buses would be brought in immediately to replace light rail for a short period, so there would be no advantage in opting for a bus-based system in the long term over a light rail system. Light rail operates in other earthquake-prone cities, such as Vancouver and Tokyo.

- Light rail is for the future — Wellington is not dense enough to support light rail.

Light rail is a congestion-free transport mode. A well-designed light rail system can scale to absorb growth in passenger numbers without the system slowing down. This can be achieved by making the light rail cars longer with additional modules and by increasing the service frequency. Unlike buses, the time taken for people to get on and off does not increase as passenger numbers increase, so travel times do not increase and remain predictable.

Light rail is a congestion-free transport mode. A well-designed light rail system can scale to absorb growth in passenger numbers without the system slowing down. This can be achieved by making the light rail cars longer with additional modules and by increasing the service frequency. Unlike buses, the time taken for people to get on and off does not increase as passenger numbers increase, so travel times do not increase and remain predictable. One multi-segment vehicle can potentially replace over 20 buses.

- Spending on urban transport is primarily for greater motor vehicle use, which attracts new traffic onto already overcrowded streets, is incompatible with good urban design, and has high environmental and social costs.

- Spending on urban transport is primarily for greater motor vehicle use, which increases congestion by attracting new traffic onto already overcrowded streets, is incompatible with good urban design, and has high environmental and social costs.

FIT’s proposal aims to double the number of public transport trips per person, while halving the carbon footprint per person from transport, by 2030. FIT proposes to achieve this by creating an integrated, congestion-free public transport network in Wellington.

FIT’s proposal aims to double public transport use, together with increased walking and cycling, and halve urban motor vehicle use, thereby halving the carbon footprint per person from transport, by 2035. FIT proposes to achieve this by creating an integrated, congestion-free public transport network in Wellington.

The downfall of double-decker buses is the slow boarding and unboarding times at busy stops. They have high capacity but will clog up the shopping streets even more than the current bus fleet does. Double-deckers work best on express routes with few stops; everywhere else, they slow the system down and cause congestion. A public transport system based around double-decker buses will not attract substantial numbers out of their cars.

The downfall of double-decker buses is the slow boarding and alighting times at busy stops. They have high capacity but will clog up the shopping streets even more than the current bus fleet does. Double-deckers work best on express routes with few stops; everywhere else, they slow the system down and cause congestion. A public transport system based around double-decker buses will not attract substantial numbers out of their cars.

A line from Johnsonville to the airport, via the railway station and hospital, is an initial work programme that satisfies these principles. The first proposed project, from the railway station to airport with connections to the commuter train network, will partially realise light rail’s benefits for Wellington and prove the concept in Wellington. A Johnsonville extension is one option; others may be better.

A line from the Airport to Johnsonville or Karori, via the hospital and railway station, is an initial work programme that satisfies these principles. The first proposed project, from the airport to railway station with connections to the commuter train network, will partially realise light rail’s benefits for Wellington and prove the concept in Wellington. Johnsonville are Karori are among several options for future extensions.

Freeing up space for light rail in Wellington’s often narrow streets will be achieved by moving on-street parking off-street, restricting vehicle access, and reducing the number of buses through the city centre. The price of central city parking will be the primary instrument for giving drivers an incentive to leave their cars at home and take public transport.

Freeing up space for light rail in Wellington’s often narrow streets will be achieved by moving on-street parking off-street, restricting vehicle access, and reducing the number of buses through the city centre. The price of central city parking and congestion charges will be the instruments for giving drivers an incentive to leave their cars at home and take public transport.

We have identified feasible and affordable options for light rail and a supporting bus network. We are confident that we have workable options, combining buses and light rail, but have not identified a best or preferred option. We propose buses and light rail on fully separated routes, both on or close to the Golden Mile.

We have identified feasible and affordable options for light rail and a supporting bus network. We are confident that we have workable options, combining buses and light rail, but have not identified a best or preferred option. We propose buses and light rail on fully separated routes, both on or close to the Golden Mile. Interchanges enable easy transfer between bus and light rail services.

The proposed solution to Wellington’s public transport problem, BRT based on double-decker buses and an all-diesel bus fleet, will improve the service, but will not bring about the step change in performance that Wellington needs. The time frame for electric buses is unknown and achieving full replacement could take much longer than expected. A proposal which ignores climate change and does not aim to reduce CO2 emissions is not fit for purpose.

Greater Wellington has acknowledged that the BRT system proposed is so low grade it is not Gold, Silver or Bronze standard, and does not even qualify as “BRT-light”. The system will make only a marginal difference to operating conditions in the city centre. It is cheap but ineffective. Even when more comprehensive BRT is implemented, it does not achieve the ride quality that a rail-based system delivers. As a result, many people are not prepared to get on a bus but they will get on light rail.

The proposed solution to Wellington’s public transport problem, BRT based on double-decker buses and an all-diesel bus fleet, will improve the service, but will do little to reduce bus congestion or bring about the step change in performance that Wellington needs. The time frame for electric buses is unknown and achieving full replacement could take much longer than expected. A proposal which ignores climate change and does not aim to reduce CO2 emissions is not fit for purpose.

While BRT can work well, Greater Wellington has acknowledged that the BRT system proposed is so low grade it is not Gold, Silver or Bronze standard, and does not even qualify as “BRT-light”. The system will make only a marginal difference to operating conditions in the city centre. It is cheap but ineffective. Even when BRT is implemented properly, it does not achieve the ride quality that a rail-based system delivers. As a result, many people are not prepared to get on a bus but they will get on light rail.

The downfall of double-decker buses is the slow boarding and unboarding times at busy stops. They have high capacity but will clog up the shopping streets even more than the current bus fleet does. The upper deck is unpopular with many passengers and does not meet accessibility criteria. Double-deckers work best on express routes with few stops; everywhere else, they slow the system down. A public transport system based around double-decker buses will not attract substantial numbers out of their cars.

The downfall of double-decker buses is the slow boarding and unboarding times at busy stops. They have high capacity but will clog up the shopping streets even more than the current bus fleet does. Double-deckers work best on express routes with few stops; everywhere else, they slow the system down and cause congestion. A public transport system based around double-decker buses will not attract substantial numbers out of their cars.

There is no prospect of improving the situation in Wellington unless additional rail investment is made. If Greater Wellington seriously wants to get more people on public transport, it will be much easier with light rail than with any bus-based system. Look at any of the 30 French cities with light rail systems and look at the patronage trends. Then look at the trends in cities that rely on buses.

There is no realistic prospect of improving the situation in Wellington unless additional rail investment is made. If Greater Wellington seriously wants to get more people on public transport, it will be much easier with light rail than with any bus-based system. Look at any of the 30 French cities with light rail systems and look at the patronage trends. Then look at the trends in cities that rely on buses.

The strength of light rail is its lack of flexibility — it says to passengers, this is a permanent route that you can rely on to base living and working decisions on. And it gives investors and businesses long term certainty. It also says to car drivers — do not park on the rails; and to road engineers — give this route priority. In short, inflexibility works.

A key strength of light rail is its lack of flexibility — it says to passengers, this is a permanent route that you can rely on to base living and working decisions on. And it gives investors and businesses long term certainty. It also says to car drivers — do not park on the rails; and to road engineers — give this route priority. In short, inflexibility works.

A line from Johnsonville to the airport, via the railway station and hospital, is the minimum work programme that satisfies these principles. The first proposed project, from the railway station to airport with connections to the commuter train network, will partially realise light rail’s benefits for Wellington and prove the concept in Wellington.

A line from Johnsonville to the airport, via the railway station and hospital, is an initial work programme that satisfies these principles. The first proposed project, from the railway station to airport with connections to the commuter train network, will partially realise light rail’s benefits for Wellington and prove the concept in Wellington. A Johnsonville extension is one option; others may be better.

Freeing up space for light rail in Wellington’s often narrow streets will be achieved by moving on-street parking off-street. The price of central city parking will be the primary instrument for giving drivers an incentive to leave their cars at home and take public transport.

Freeing up space for light rail in Wellington’s often narrow streets will be achieved by moving on-street parking off-street, restricting vehicle access, and reducing the number of buses through the city centre. The price of central city parking will be the primary instrument for giving drivers an incentive to leave their cars at home and take public transport.

Overseas experience shows that investing in light rail creates an economic halo around the stations along the corridor. The area within about 400 metres of a station becomes a focus for commercial, social and residential development. When stations are placed about 700–800 metres apart — closer together in the city centre, further apart in the suburbs, but always at major destinations — the result is a rich and vibrant urban environment.

Overseas experience shows that investing in light rail creates an economic halo around the stations along the corridor. The area within about 400 metres of a station becomes a focus for commercial, social and residential development. When stations are placed about 700–800 metres apart — closer together in the city centre, further apart in the suburbs, but always at major destinations — the result is a rich and vibrant urban environment. This economic halo in turn drives light rail revenue growth.

The identified route is within the area defined in the N2A study, but does not run by the Basin Reserve. Recent experience suggests it will be challenging to find an acceptable Basin route, and multi-segment light rail cars can be difficult on large, multi-lane roundabouts. This corridor is more suited to buses, with no particular reason to run a high-capacity light rail route that way.

Light rail costs have fallen in recent years, and in 2014 the International Railway Journal quoted €25–30m per kilometre ($42–51m/km) for a typical line in France. Now Besançon, France has opened a new line for €17.5m/km ($30m/km). Using these figures as a guide, we consider the costs set out in Comparative costs of a and b options are reasonable and conservative. We have assumed:

The identified route is within the area defined in the N2A study, but avoids the Basin Reserve. Recent experience suggests it will be challenging to find an acceptable Basin route, and multi-segment light rail cars can be difficult on large, multi-lane roundabouts. This corridor is more suited to buses, with no particular reason to run a high-capacity light rail route that way.

Light rail costs have fallen in recent years, and in 2014 the International Railway Journal quoted €25–30m per kilometre ($42–51m/km) for a typical line in France. Now Besançon, France has opened a new line for €17.5m/km ($30m/km). Using these figures as a guide, we consider the costs set out in Comparative costs of a and b options are reasonable and conservative — civil engineering works tend to cost more in New Zealand than overseas. We have assumed:

FIT acknowledges there are technical challenges in the Constable St option, but is confident that the engineers can find workable solutions. Clearly, the cost saving would be considerable — enough to fund over 5km of light rail construction. FIT suggests that the money would deliver better value if spent on extending the line to Johnsonville, where tunnelling is unavoidable.

FIT acknowledges there are technical challenges in the Constable St option, but is confident that the engineers can find workable solutions. Clearly, the cost saving would be considerable — enough to fund over 5km of light rail construction. FIT suggests that the money would deliver better value if spent on extending the line north, e.g. to Johnsonville, where tunnelling is unavoidable.

(:description The current approach to public transport in Wellington is no longer tenable. Proposed investments in the bus system will bring welcome improvements, but will not achieve the step change in public transport performance that Wellington needs. Our aim is to double ridership by progressively building a world-class light rail system in Wellington city. The first stage, between the Railway Station and the Airport, via the Hospital, can be completed by 2030, for an estimated cost as low as $450 million. :)

The current approach to public transport in Wellington is no longer tenable. Proposed investments in the bus system will bring welcome improvements, but will not achieve the step change in public transport patronage that Wellington needs. Our aim is to double ridership by progressively building a world-class light rail system in Wellington city. The best way to reduce congestion in Wellington is to encourage people out of private cars and buses onto light rail. The first stage, between the Railway Station and Miramar, via the Hospital and Airport, could be completed by 2027, for an estimated cost between $570 and $750 million, depending on the route.

(:typeset-page headingcolor=ForestGreen fontset=kepler colorlinks=on subtitle="A Strategy and Implementation Plan" autonumber=1 toc=on colophon=off parasep=number watermark=draft :)

What’s the strategic context for the proposal?

FIT stands for fair, intelligent transport. FIT’s vision for Wellington is a modern and vibrant city designed around the needs of people. Wellington will be:

- A healthy, safe city where the built environment and transport system enhance the unique character and beauty of the harbour capital;

- A city with reliable, low-cost, fast and convenient electric public transport that takes people where they want to go; and

- A city that actively promotes walking, cycling and public transport to reduce transport costs, encourage physical exercise and mitigate against pollution and climate change.

FIT proposes investing in light rail as essential infrastructure for realising this vision. Light rail is a form of public transport designed to provide fast, efficient, clean service to people living in urban areas. It uses electric rail cars, running on tracks in existing roads, separated from other road traffic. It is designed to carry lots of people, with connections to buses and suburban trains at major interchanges. One multi-segment light rail vehicle can do the work of 5 or more buses.

This paper sets out the case for light rail in Wellington.

What are we trying to do? Articulate the objectives using no jargon.

The current transport system over-privileges the faster movement of private motor vehicles, to the detriment of a reliable, fast and convenient public transport system. There are 3 problems which make this approach no longer sustainable.

- International agreement on climate change requires a new approach to sustainable transport that eliminates burning of fossil carbon by 2050 or shortly thereafter (urban traffic uses almost 20% of New Zealand’s fossil fuel).

- Slow and unreliable inner-city public transport, with few and poor-quality transfers, limits options, discourages patronage, frustrates wider use of walking, and increases costs.

- Spending on urban transport is primarily for greater motor vehicle use, which attracts new traffic onto already overcrowded streets, is incompatible with good urban design, and has high environmental and social costs.

When measured against the public transport systems in other New Zealand cities, such as Auckland, Christchurch and Dunedin, Wellington has a good public transport system, with good patronage. However, Wellington has a long way to go to measure up against the public transport systems in other cities around the world. The potential to grow patronage is huge, but to achieve this growth, we need to make public transport an attractive and compelling alternative to the private car. This means making public transport more reliable and predictable, improving connectivity between services, and offering competitive fare structures.

FIT’s proposal aims to double the number of public transport trips per person, while halving the carbon footprint per person from transport, by 2030. FIT proposes to achieve this by creating an integrated, congestion-free public transport network in Wellington.

How is it done today, and what are the limits of current practice?

The investment logic behind Greater Wellington’s indicative business case for introducing BRT identifies three problem areas: failure to maximise the capacity of key corridors for moving people and goods; increasing congestion within a constrained corridor that will continue to impact on levels of service; and failure to grow patronage due to unattractive and unreliable public transport services.

The problem of moving traffic is primarily a peak hour one. Maximising capacity will never be achieved by expanding road space along the primary route from Ngauranga to the airport, nor by the proposals for BRT on key routes. Efficient movement of people and goods will only be achieved by introducing measures aimed at reducing traffic volumes entering the city, particularly at peak hours. The best way to reduce congestion is to restrict parking and road space for private motor vehicle traffic.

The second problem is self-evident but current proposals, particularly the new motorways north of the city, will make the situation worse. When the Kapiti Expressway and Transmission Gully are finished, Wellington will see an estimated 11,000 extra vehicles entering the city on a daily basis. This increase will negate any potential improvement on levels of service.

The proposed solution to Wellington’s public transport problem, BRT based on double-decker buses and an all-diesel bus fleet, will improve the service, but will not bring about the step change in performance that Wellington needs. The time frame for electric buses is unknown and achieving full replacement could take much longer than expected. A proposal which ignores climate change and does not aim to reduce CO2 emissions is not fit for purpose.

Greater Wellington has acknowledged that the BRT system proposed is so low grade it is not Gold, Silver or Bronze standard, and does not even qualify as “BRT-light”. The system will make only a marginal difference to operating conditions in the city centre. It is cheap but ineffective. Even when more comprehensive BRT is implemented, it does not achieve the ride quality that a rail-based system delivers. As a result, many people are not prepared to get on a bus but they will get on light rail.

BRT is a poor substitute for, and rarely produces anything like the benefits of, light rail. Whenever it gets difficult the traffic engineers give up and send the bus into the general traffic lanes — if it’s a light rail car, the system has to be engineered from end to end. Wellington cannot afford to waste time and money developing solutions that won’t produce the benefits that light rail can deliver.

The downfall of double-decker buses is the slow boarding and unboarding times at busy stops. They have high capacity but will clog up the shopping streets even more than the current bus fleet does. The upper deck is unpopular with many passengers and does not meet accessibility criteria. Double-deckers work best on express routes with few stops; everywhere else, they slow the system down. A public transport system based around double-decker buses will not attract substantial numbers out of their cars.